Bridging the gap between users and scientists: challenges of climate service production in a central European case study

Marion Zilker

Inga Beck

Ralf Ludwig

Gunnar Braun

The exchange of adaptation-relevant climate information between scientists, stakeholders and the general public is marked by a gap between user needs and provided information. This multidimensional gap can be described in terms of temporal and spatial scales, variable selection, specificity of needs, and consideration of uncertainty. To bridge this gap, we argue for a multi-way format of co-creating (a) a viable form of information exchange and (b) the relevant information itself, while recognising the needs of users and capabilities of providers. This is to ensure that relevant information can be provided to users who are motivated to apply them. We here describe the offer-need gap in the Main River catchment (central Germany), which is increasingly characterized by climate change and user-induced water scarcity, and present a framework for bridging the gap in stakeholder dialogues.

- Article

(1678 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

In recent years, more frequent extreme events triggered severe impacts, damages and fatalities in Bavaria (Germany), like extreme precipitation and floods in 2024, 2021 and 2016, droughts in 2022–2023 and 2018–2020 and prolonged heat periods in 2022, 2018 or 2015 (e.g., Munich RE, 2024; StMWi, 2025; Schröter et al., 2024; Vogel et al., 2019, an der Heiden, 2023). These events became more frequent or intense due to climate change (Schröter et al., 2024; Leach et al., 2020; Vogel et al., 2019; Tradowsky et al., 2023). Associated impacts were prevalent in agriculture, infrastructure and transportation, health care, water management, energy production and supply (Vogel et al., 2019; LfU, 2017, Sodoge et al., 2024). Stakeholders in these sectors hence have strong interests in building resilience, e.g., by reducing vulnerability via improved adaptation measures.

To do so effectively, they can refer to high-quality science-based climate information, i.e., climate services. Climate services can be based on observational or modelled weather and climate data, as for example provided by the Bavarian Climate Information System (“Bayerisches Klimainformationssystem, BayKIS”, LfU, 2024), the Climate Fact Sheets by the Climate Service Center Germany (GERICS, 2026) and the Bavarian Environmental Agency (LfU, 2026), or the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) by the European Union's Earth Observation Programme (ECMWF, 2026). The German Climate Adaptation Law (“Bundes-Klimaanpassungsgesetz, KAnG”) specifically addresses the need for data-based adaptation by mandating the data that federal states must consider when developing their adaptation strategies (BGBl. I., 2023). On a European level, the European Research and Innovation Roadmap for Climate Services aims at providing a framework for fostering an impactful climate services sector during the Horizon 2020 programme (Street, 2016).

Climate services are increasingly required to go beyond purely user-tailored data bases for adaptation management, by acknowledging their design process, i.e., the trans-disciplinary knowledge exchange between science and users (e.g., Jacobs and Street, 2020; Findlater et al., 2021). Reconciling offered services and requested information and creating meaningful use thereof though remains challenging. While climate scientists tend to overestimate the usability of their data in real world problems, potential users often lack training in climate science, thus failing to see chances and limitations of the data (Jacobs and Street, 2020). This is reflected in two different paradigms and thence a mismatch in climate service creation: supply-driven, i.e., based on improvement of available data, and demand-driven, i.e., based on improvement of decision-making (Findlater et al., 2021; Raaphorst et al., 2020). Our contribution states and describes a multi-dimensional gap between information required by users and data produced by scientists which can result in delayed or inhibited decision-making and subsequent implementation of possible solutions (Weaver at al., 2013).

Our assessment is embedded in the frame of the European Union's Horizon 2020 innovation action “ARSINOE – Climate Resilient Regions through Systemic Solutions and Innovations” (https://www.arsinoe-project.eu, last access: 20 January 2026). ARSINOE aims to improve resilience by designing replicable tool boxes for climate adaptation in nine demonstrator regions across Europe, one of them being the Main River Catchment in Northern Bavaria (Germany). Among others, the project facilitates exchange platforms for stakeholders. For their benefit, this study proposes a framework to bridge the gap between users and producers of climate services within a co-creation process.

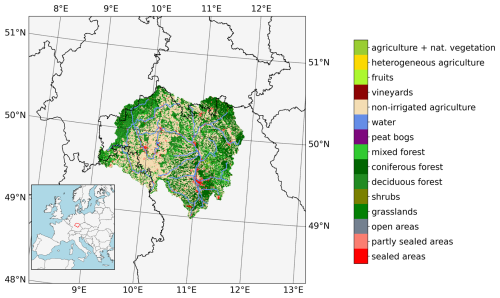

2.1 The Main River Case Study in ARSINOE

The Main River catchment in central Germany (Fig. 1) is strongly affected by intersectoral challenges related to water scarcity and water competition. This study focuses on the upper 406 km of the Main River, the largest tributary to the Rhine, up to the gauging station Kleinheubach. Its catchment covers 21 519 km2 with highly diversified and specialized land use (e.g., horticulture and viniculture) and urban centres like Nuremberg and Würzburg. The population within the catchment area amounts to approximately 3.8 million inhabitants. Additionally, the Main River catchment is embedded in the complex interregional Main-Danube water transfer system, supporting navigation, hydropower and tourism.

The Main River catchment belongs to the warmest and driest regions of Germany with annual mean temperatures of 8–9 °C and annual precipitation sums of 600–800 mm (1971–2000; LfU, 2024). Climate change projections for the region suggest longer, more frequent and intense droughts that are increasingly associated with extreme temperatures (Böhnisch et al., 2021, 2025), a doubling of heavy precipitation days (LfU, 2024), a seasonal shift of precipitation patterns towards moister winters and drier summers (Böhnisch et al., 2021), higher risks for fire weather (Miller et al., 2024) and the intensification of floods (Willkofer et al., 2024), if no mitigation is implemented. In addition to altered water availability, water demands by, e.g., agriculture, (public) water supply or energy production change as well (e.g., Destatis, 2025). The Main River region thus exhibits high vulnerability due to accumulated infrastructure, economy and urban centres, but also high exposure to hazards fuelled by climate change, both paired with a limited adaptive capacity to climate change impacts.

To address these challenges and provide innovative solutions for climate adaptation, the project ARSINOE initiated stakeholder dialogues in the region, in compliance with the systems innovation approach (Mulgan and Leadbeater, 2013). Following a stakeholder mapping, so-called Living Labs, i.e., platforms for exchange (Moujan et al., 2023), were established in the Main River region to distil key challenges, a vision of a sustainable future and pathways to resilience within the water-energy-food nexus (see Cruz-Perez et al., 2023, for a detailed description of the methodology). The pathways include nature-based solutions, citizen science initiatives, novel technologies or governance schemes and financial instruments. Participants from regional enterprises, authorities and associations contributed to the Living Lab “Bayerischer Main” in three workshops to develop a shared understanding of challenges and potential solutions.

2.2 Workshops on Climate Services

Stakeholder dialogues during our Living Lab workshops showed the need of and interest for climate services. Therefore, Living Lab participants and further stakeholders were invited to two additional workshops (online, September 2023; Nuremberg/in-person, November 2023) for specific discussions on climate services. Participants were affiliated to governmental bodies at local and regional level, local public utilities, environmental NGOs, agricultural associations or water management authorities. Consequently, their concerns to be addressed by climate services were highly heterogeneous. The goal of the workshops was to establish the awareness of potential users on climate service availability and to adequately frame users' specific needs. Climate or hydro services were introduced as any kind of weather, climate or hydrological information derived from observations and model projections, provided by either the attending scientists or public sources and portals with the purpose of facilitating transformative decision-making. Guiding questions in the workshops addressed the issue to be targeted by climate services, the type of required climate services, identifying concrete users and the format of climate services. In addition to group discussions during the workshops, bilateral conversations afterwards were set up to refine the discussion results.

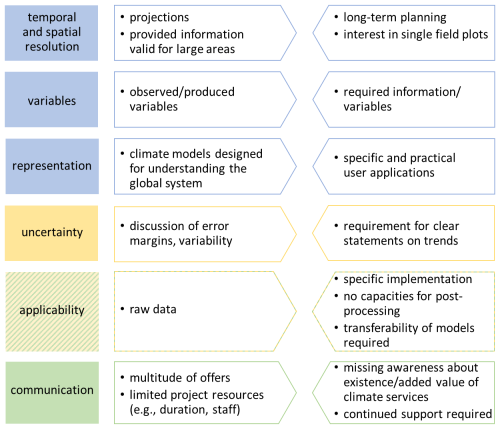

3.1 Identification of a multi-dimensional offer–need gap

The discussions during and after the workshops revealed a distinctive gap between potential users of climate services and their providers in the Main River catchment. This gap, the “valley of death” between users and providers (Swart et al., 2021), encompasses multiple dimensions (Fig. 2) which are often reported in literature (e.g., Jacobs and Street, 2020; Findlater et al., 2021; Swart et al., 2021; Bojovic et al., 2021). In parts, the gap identified in the case study overlaps with the stakeholder-related “usability gaps” by Raaphorst et al. (2020). Some of the gap dimensions found in the Main River catchment refer to data-related aspects, such as the suitability of the data (e.g., requested and available variables or their temporal and spatial resolutions) or certainty of statements (blue). Others relate to the applicability of the data, such as data-related uncertainty, the degree to which a concrete problem can be addressed by the data, or the level of postprocessing the data before it can be employed by non-data scientist users (yellow). The third category addresses communication between users and providers (green): While a plethora of (raw) climate and hydrological data is produced and provided by research institutes or authorities, the available information are hardly known, difficult to use or inadequate for a given question and thus not of interest to potential users. Finding a common framing for the question of interest is also challenging. Furthermore, updating and maintaining climate services require long-term resources (e.g., support team, data access/storage, budget, network, progress monitoring) which can hardly be ensured if climate services are produced in (research) project contexts with frequently changing staff, limited time, IT infrastructure and financial resources.

Figure 2Dimensions of the gap between requests of potential climate service users (right) and providers (left) corresponding to different categories: technical/data-related (blue), application (yellow), exchange (green).

In general, the gap originates from different claims on data: On the one hand, experiments and campaigns that produce climate data typically aim at holistically monitoring, describing or understanding climate and hydrology. Using the data for climate services is decided ex-post in these cases (cf. the “loading dock mentality” by Jacobs and Street, 2020). However, this data can be post-processed in collaboration with stakeholders (e.g., Koutroulis et al., 2015). Potential users, on the other hand, are confronted with decision making in a concrete, localized and personal setting. They require specialized and processed information for implementing adaptation (cf. “projection shopping” by Jacobs and Street, 2020), but not necessarily simply “better data” (Findlater et al., 2021). Furthermore, stakeholders are often unaware of available services. Consequently, many stakeholders reported in the workshops that they did not use climate services for decision-making (yet).

3.2 Bridging strategy: structured and iterative co-creation

Based on the workshop discussions, we collected and refined iteratively several topics of interest to the stakeholders in dedicated follow-up meetings. Among these topics were meteorological hazards (extreme heat, compound hot and dry events, heavy precipitation) and hydrological indicators (amount of discharge, water temperatures, sediment transport, groundwater recharge), but also ecological or phenological information. Stakeholders asked for their temporal characteristics (seasonality, diurnal variation) or occurrence probabilities. Potential areas of climate service application covered risks to biodiversity, to water availability or quality, or to vine and crop yields, adaptation of infrastructure or adaptation at municipal level in accordance with federal laws. Stakeholders were also interested in the reliability of models, of scenario-based projections and of their own assumptions on processes in the context of climate change. Furthermore, the concept of climate services itself was scrutinized (e.g., limitations, climate services compared to personal experience, usage for communication purposes). The requests thus went beyond the application of raw data only.

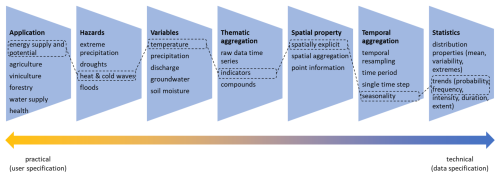

One strategy for bridging the gap between users and providers consists of openly communicating and addressing its dimensions. Therefore, we converted the above-mentioned topics into a framework to guide co-creation processes in ARSINOE (Fig. 3). It describes possible choices within a spectrum from practical applications to data processing.

Figure 3Framework for considering multiple dimensions when designing climate and hydro services, including selected characteristics. Black dashed lines illustrate an example combination of characteristics for defining a climate service that results in seasonal trend maps of heating/cooling degree days.

A climate service like cooling/heating degree days for energy suppliers may thus be described in terms of the topic (energy supply and potential), the hazards to be considered (heat and cold periods), the variables to describe the hazard (temperature), the decision for defining an indicator as opposed to compound events or using raw time series, the spatial and temporal aggregation (seasonal maps) and the statistics of interest (frequency trends). Temporal and spatial properties refer to the selection of single time steps and periods (e.g., historic, present, future, counterfactual), locations and areas, and the resampling to requested time steps (e.g., hours, days, years) or spatial resolutions. Last, choices on the statistical processing allow to tailor data further towards specific use cases (e.g., trends of extreme events, inter-annual variability). Besides the categories described in Fig. 3, more technical issues, such as the data source (e.g., observations, model projections), data format or the way of conveying and providing climate services, have to be agreed upon. The framework structure, the categories and the elements from which to choose can be adjusted to the context it is used in.

The framework is also intended to ascertain a common understanding of the problem to be addressed, by breaking down the aspects of complex climate services to modular building blocks which can be “translated” between users and producers. These elements can then be combined to address varying levels of complexity once the specific needs are defined.

Aside from structuring the discussion process as suggested in Fig. 3, a more encouraging and explanatory communication on existing climate services is required to raise awareness of climate services and their limitations (e.g., data uncertainty) or applicability among stakeholders. A central component of this process is a tool or “translation sheet” that helps convert stakeholder questions or policy demands into scientific terms to enable data providers to understand what kind of information is needed, whether it can be derived from existing datasets, or whether new data must be collected. This translation is often just as important as the data itself, as it facilitates mutual understanding between data providers and users. Besides providing data, scientists need to understand how decision-making processes work: who the stakeholders are, what decisions they make, how those decisions are made, and why. This understanding is crucial to ensure that the information delivered is truly fit for purpose. To succeed in this task, engagement, involvement during the coproduction process and empowerment of stakeholders for using climate services is required (Bojovic et al., 2021).

The participants of the climate service workshops included this point also in their feedback. Stakeholders valued particularly the introduction to climate services during the workshops and the opportunity for fostering fact-based opinion forming and decision-making. However, besides missing awareness, other factors may also contribute to not using climate services, like data that is not suitable for the concrete problem, missing ability and technical options to use the data or a culture of valuing personal experience on specific field plots more than generalized and externally provided statements about the region. The participants were positive about their perspectives and concerns being acknowledged in an active dialogue. Concrete discussions were preferred over general presentations. The workshops thus allowed to grow mutual understanding of data and contexts in which requests are formulated as a foundation for successful exchange of climate services.

To avoid the Main River region being pushed beyond its resilience thresholds, intersectoral adaptation measures must be implemented at a higher pace. For local stakeholders, climate services can support fact-based decision-making towards a resilient future by providing a data base for current states (monitoring) or possible futures (scenarios). Climate scientists need to find ways to efficiently convey the information they have, so it can inform real world applications. This includes interdisciplinary work with social scientists to ameliorate the exchange process and foster transformation (Jacobs and Street, 2020; Findlater et al., 2021). By engaging in cooperation and co-creation, stakeholders can benefit from up-to-date information, and scientists can make their work more impactful, including the opportunity to get practitioners' feedback on its usability and raising its visibility (Bojovic et al., 2021).

However, there is a multidimensional discrepancy between commonly available scientific information and user requirements. The discrepancy can be addressed by the framework presented here, by using ex-ante co-creation or ex-post co-processing, if the first option is economically infeasible, and a suitable communication process. The value of the dimensions lies in realizing different aspects of potential misunderstanding when discussing climate services. The framework is suggested for a stage when stakeholders and data providers already engage in development of quantitative data services. Guidance by the framework categories can be adjusted depending on the technical proficiency of the users. The specific characteristics of the framework are tied to results from this case study, but the structure is transferable to other regions as well.

Lastly, climate services also tell stories about changes taking place in the region. Thereby, they can serve as communication tools to enhance public acceptance of adaptation or mitigation measures.

For the main analysis, no formal data was used. The map in Fig. 1 is based on freely available Corine Land Cover data (EEA, 2020) available at https://doi.org/10.2909/960998c1-1870-4e82-8051-6485205ebbac.

AB compiled the content (dimensions, framework) and prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors. MZ, RL and GB conducted the Living Lab workshops and Climate Services workshops. All authors were part of climate services discussions in the project, revised and reviewed the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “EMS Annual Meeting: European Conference for Applied Meteorology and Climatology 2024”. It is a result of the EMS Annual Meeting 2024, Barcelona, Spain, 2–6 September 2024. The corresponding presentation was part of session ES2.1: Communication and media.

This research has been supported by the European Commission, EU Horizon 2020 Framework Programme (grant no. 101037424).

This paper was edited by Tanja Cegnar and reviewed by Sam Pickard, Paula Williams, and one anonymous referee.

an der Heiden, M.: Neubestimmung der Prädiktionsintervalle zur Schätzung der hitze-bedingten Mortalität – Kommentar und Erläuterung zu “Hitzebedingte Mortalität in Deutschland” (Epidemiologisches Bulletin 42/2022), Epid. Bull., 26, 14–16 https://doi.org/10.25646/11580, 2023.

Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt (LfU): Sturzfluten und Hochwasserereignisse Mai/Juni 2016, https://files.hnd.bayern.de/berichte/lfu_SturzflutenMaiJuni2016.pdf (last access: 20 January 2026), 2017.

Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt (LfU): Bayerisches Klimainformationssystem, https://klimainformationssystem.bayern.de/ (last access: 20 January 2026), 2024.

Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt (LfU): Die Klimafaktenblätter des LfU, https://www.lfu.bayern.de/klima/klimawandel/klimafaktenblaetter/index.htm, last access: 20 January 2026.

Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Wirtschaft, Landesentwicklung und Energie (StMWi): Naturgefahren in Bayern, https://www.stmwi.bayern.de/wirtschaft/elementarschadenversicherung/naturgefahren-in-bayern/ (last access: 20 January 2026), 2025.

Böhnisch, A., Mittermeier, M., Leduc, M., and Ludwig, R.: Hot spots and climate trends of meteorological droughts in Europe: assessing the percent of normal index in a single-model initial condition large ensemble, Frontiers in Water, 3, https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2021.716621, 2021.

Böhnisch, A., Felsche, E., Mittermeier, M., Poschlod, B., and Ludwig, R.: Future Patterns of Compound Dry and Hot Summers and Their Link to Soil Moisture Droughts in Europe, Earth's Future, 13, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024EF004916, 2025.

Bojovic, D., St. Clair, A. L., Christel, I., Terrado, M., Stanzel, P., Gonzalez, P., and Palin, E. J.: Engagement, involvement and empowerment: Three realms of a coproduction framework for climate services, Global Environmental Change, 68, 102271, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102271, 2021.

Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl.): Bundes-Klimaanpassungsgesetz (KAnG), Bundesgesetzblatt Nr. 393, https://www.recht.bund.de/bgbl/1/2023/393/VO (last access: 20 January 2026), 2023.

Climate Service Center Germany (GERICS): Fact-Sheets, https://www.gerics.de/products_and_publications/fact_sheets/index.php.de, last access: 20 January 2026.

Cruz-Pérez, N., Rodríguez-Alcántara, J. S., Rodríguez-Martín, J., Moujan, C., La Jeunesse, I., and Santamarta, J. C.: Living labs as participatory and community learning applied to regional development, in: Proceedings of EDULEARN23 Conference 3–5 July 2023, Palma, Mallorca, Spain, https://doi.org/10.21125/EDULEARN.2023.1707 2023.

European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF): Copernicus Climate Change Services, https://climate.copernicus.eu, last access: 20 January 2026.

European Environment Agency (EEA): CORINE land cover 2018 (raster), Europe, 6 yearly, European Environment Agency (EEA) [data set], https://doi.org/10.2909/960998c1-1870-4e82-8051-6485205ebbac, 2020.

Findlater, K., Webber, S., Kandlikar, M., and Donner, S.: Climate services promise better decisions but mainly focus on better data, Nature Climate Change, 11, 731–737, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01125-3, 2021.

Jacobs, K. and Street, R.: The next generation of climate services, Climate Services, 20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2020.100199, 2020.

Koutroulis, A. G., Grillakis, M. G., Tsanis, I. K., and Jacob, D.: Exploring the ability of current climate information to facilitate local climate services for the water sector, Earth Perspectives 2, 6, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40322-015-0032-5, 2015.

Leach, N. J., Li, S., Sparrow, S., van Oldenborgh, G. J., Lott, F. C., Weisheimer, A., and Allen, M. R.: Anthropogenic Influence on the 2018 Summer Warm Spell in Europe: The Impact of Different Spatio-Temporal Scales, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 101, S41–S46, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-19-0201.1, 2020.

Miller, J., Böhnisch, A., Ludwig, R., and Brunner, M. I.: Climate change impacts on regional fire weather in heterogeneous landscapes of central Europe, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 24, 411–428, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-24-411-2024, 2024.

Moujan, C., La Jeunesse, I., Akinsete, E., and Guittard, A.: Reframing Transition Pathways and Values Through System Innovation Across 9 European Regions, in: Proceedings of the OpenLivingLab Days Conference 2023, edited by: European Networks of Living Labs, OpenLivingLabDays 2023 (OLLD), Zenodo [conference proceeding], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10948803, 2023.

Mulgan, G. and Leadbeater, C.: Systems Innovation, Nesta, London, https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/systems_innovation_discussion_paper.pdf (last access: 20 January 2026), 2013.

Munich RE: Severe thunderstorms and flooding drive natural disaster losses in the first half of 2024 https://www.munichre.com/en/company/media-relations/media-information-and-corporate-news/media-information/2024/natural-disaster-figures-first-half-2024.html (last access: 20 January 2026), 2024.

Raaphorst, K., Koers, G., Ellen, G. J., Oen, A., Kalsnes, B., van Well, L., Koerth, J., and van der Brugge, R.: Mind the Gap: Towards a Typology of Climate Service Usability Gaps, Sustainability, 12, 1512, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041512, 2020.

Schröter, J., Knauf, J., Tivig, M., Lorenz, P., Sauerbrei, R., and Kreienkamp, F.: Attributionsstudie zu den Niederschlagsereignissen in Bayern und Baden-Württemberg Mai–Juni 2024, Bericht des Deutschen Wetterdienstes, https://doi.org/10.5676/dwd_pub/attribution/2024_02, 2024.

Sodoge, J., Kuhlicke, C., Mahecha, M. D., and de Brito, M. M.: Text mining uncovers the unique dynamics of socio-economic impacts of the 2018–2022 multi-year drought in Germany, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 24, 1757–1777, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-24-1757-2024, 2024.

Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis): Wassergewinnung, Einwohner mit Anschluss an die öffentliche Wasserversorgung, Wasserabgabe: Bundesländer, Jahre 2007–2022 (Code: 32211-0001), Statistisches Bundesamt [data set], https://www-genesis.destatis.de/datenbank/online/url/86e73ef4 (last access: 20 January 2026), 2025.

Swart, R., Celliers, L., Collard, M., Prats, A. G., Huang-Lachmann, J.-T., Sempere, F. L., de Jong, F., Máñez Costa, M., Martinez, G., Velazquez, M. P., Martín, A., Segretier, W., Stattner, E., and Timmermans, W.: Reframing climate services to support municipal and regional planning, Climate Services, 22, 100227, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2021.100227, 2021.

Street, R. B.: Towards a leading role on climate services in Europe: A research and innovation roadmap, Climate Services, 1, 2–5, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2015.12.001, 2016.

Tradowsky, J. S., Philip, S. Y., Kreienkamp, F., Kew, S. F., Lorenz, P., Arrighi, J., Bettmann, T., Caluwaerts, S., Chan, S. C., De Cruz, L., de Vries, H., Demuth, N., Ferrone, A., Fischer, E. M., Fowler, H. J., Goergen, K., Heinrich, D., Henrichs, Y., Kaspar, F., Lenderink, G., Nilson, E., Otto, F. E. L., Ragone, F., Seneviratne, S. I., Singh, R. K., Skålevåg, A., Termonia, P., Thalheimer, L., van Aalst, M., Van den Bergh, J., Van de Vyver, H., Vannitsem, S., van Oldenborgh, G. J., Van Schaeybroeck, B., Vautard, R., Vonk, D., and Wanders, N.: Attribution of the heavy rainfall events leading to severe flooding in Western Europe during July 2021, Climatic Change, 176, 90, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03502-7, 2023.

Vogel, M. M., Zscheischler, J., Wartenburger, R., Dee, D., and Seneviratne, S. I.: Concurrent 2018 hot extremes across Northern Hemisphere due to human-induced climate change, Earth's Future, 7, 692–703, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EF001189, 2019.

Weaver, C. P., Lempert, R. J., Brown, C., Hall, J. A., Revell, D., and Sarewitz, D.: Improving the contribution of climate model information to decision making: the value and demands of robust decision frameworks, WIREs Clim. Change, 4, 39–60, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.202, 2013.

Willkofer, F., Wood, R. R., and Ludwig, R.: Assessing the impact of climate change on high return levels of peak flows in Bavaria applying the CRCM5 large ensemble, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 28, 2969–2989, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-28-2969-2024, 2024.